o.i.p.b.g. central website . com

göööööd tidings 2 u

sign or trace?: derrida on a semiology of presence to a grammatology of différance

a straightforward academic essay written for a postmodernist philosophy course.

✿♥✿♥✿

sign or trace?

does meaning rest upon language? or, more fundamentally, does meaning rest upon signification? if so, semiology – the study of signification and meaning – comes before and comprehends all of our sciences and studies.

jacques derrida indeed sees writing (a term which has specific implications that will be explained further, but for now should be understood as a system of differences out of which meaning is emergent) as comprehending language and all intellectual endeavours. it comes as no surprise, however, that semiology as we know it, which is famously associated with the late 19th century father of the term ferdinand de saussure, is bound up with the western philosophical tradition from whence it came. in a heideggerian vein derrida seeks to deconstruct what he sees as an indefensible metaphysics of presence1 implicit within semiology’s genealogy. given the utterly foundational nature of semiology’s object of study, this deconstruction would in fact alter the very presuppositions upon which semiology is based down to the concepts of sign and science. as such, this deconstructed semiology, purged of the metaphysics of presence, can no longer be a semiology at all. a study of grammatology would take its place.

the idea of the sign, for derrida, is saturated in presence, particularly for the notion of the transcendental signified embedded within it. thus, the sign and its concepts, including signification, cannot serve the purposes of grammatology. instead, derrida understands semiology in terms of the trace to subvert the notion of the transcendental signified and the metaphysics of presence implicit in it. the trace in effect redirects the emergence of meaning from the transcendental signified (and thus from presence) to différance2 (which is not present – which, in fact, does not even have an ontological status) or, put otherwise, the play of differences within writing.

deconstruction

the implications of this seemingly modest shift from the sign to the trace are manifold. absent the transcendental signified, meaning is emergent out of the play of differences within a specific system of writing: the sense of the same “word” is unique from language to dialect to idiolect. thus, our presuppositions on the nature of reality and those dichotomies, cultural or otherwise, that we once supposed transcended language and culture are now open to deconstruction and to reconstruction. perhaps most famously, this strategy of deconstruction has been applied to gender by contemporary philosopher judith butler. if male and female, alongside the host of other concepts associated with these terms, are not grounded in a transcendental signified, we may refashion these notions by deconstructing and reconstructing the web of other signifiers through which they emerge.

saussure, semiology

before moving on to derrida’s deconstruction and the shift from the sign to the trace, we must first understand the basis of saussure’s semiology, which is based fundamentally on two concepts:

1. the sign as a bipartite construction composed of the signifier – the component of the sign which presents itself to the senses i.e., the material written word or sound of the voice – and the signified – the concept or the thing being referred to i.e., the ideal or real baklava, internet, or circle.

2. the arbitrariness of the sign. the signifier may be fashioned more or less any which way we please. for example, the sound of a word is arbitrary as is evidenced by the fact that the “same signified” is referred to by different signifiers – different sounds, in the case of speech – in different languages.

many of the notions implicit in the above two principles will become suspect later on. however, the arbitrariness of the sign remains central to derrida, albeit not without some considerable tinkering. for if the signifying component of the sign is arbitrary then it is interchangeable and language is fundamentally, at least in part, a structure (semiology is, after all, a form of structuralism) of “internal” relations – not merely a one-to-one translation of some “real” existing “outside” of language. for saussure, this applies at the very least to the signifier: “the linguistic signifier […] is not [in essence] at all phonic but incorporeal – constituted not by its material substance but uniquely by the differences that separate its sound-image from all others”3. derrida, however, takes issue with the distinction between the signified and the signifier, and as a result we move not only from sign to trace but also from arbitrariness to différance.

the transcendental signified

“to the [epoch of the logos] would belong the difference between signified and signifier.”4

if, as saussure claims, the signifying component of language is a system of internal relations, then to what does the signified refer? if meaning is emergent out of the play of differences within writing, then how is meaning also simultaneously derived from some external transcendental signified? this statement would appear contradictory. thus, in a sense, there are two saussures: the saussure of the arbitrariness of the sign and the differential character of signification and the saussure of the bipartite sign the transcendental signified.

what’s more, this contradiction is not simply an inconspicuous lapse in saussure’s logic; it is in fact bound up with and reproductive of the metaphysics of presence. bundled with the signifier/signified binary, a distinction whose roots do in fact go back at least to the ancient greek signans/signatum5, is an ontological distinction between the sensible and the intelligible. in combination with a christian theology that associates the sensible with material life on earth and the intelligible with immaterial divinity, this dichotomy produces a preferential treatment of speech over writing. particularly in the european tradition, with its (nominally) phonetic alphabets, writing is conceived of as a sign of a sign – a signification of the sound of a word which is in turn a signification of the real. twice removed from “the real”, twice removed from the signified, twice removed from the divine. thus, spoken language is perceived to be closer to the intelligible signified and, by extension, closer to god.

thus, saussure’s contradiction is suspect not only due to its logical inconsistently, but perhaps more so for its complicity within the tradition of the metaphysics of presence. in order to avoid this contradiction and to subvert the metaphysics of presence implicit in it, derrida asserts différance over arbitrariness as that which generates meaning within what semiology would call language, but derrida calls writing. simultaneously, saussure’s notion of the sign is displaced. in turn, though not as a replacement, we get the trace.

the trace

“[the sound-image] is not the material sound, a purely physical thing, but the psychic imprint of the sound, the impression that it makes on our senses”6 – saussure

in developing a semiology emptied out of presence, though inevitably trapped within it7, and which is consequently no longer a semiology but a grammatology, derrida latches onto and modifies the differential nature of signification put forth by saussure.

if the meaning of a signifier arises out of its differences from other signifiers, then we enter a play of différance, where the conventionally expected presence of the signified is continually deferred. we search for the meaning of one signifier in a whole host of other signifiers and look for the meanings of those signifiers in yet another set of signifiers ad infinitum. presence never arrives. yet despite this, we find meaning in speech, writing, and symbols. how is this so? meaning is emergent exactly out of that play of différance.

each signifier, then, is marked by that which it is not, by the other. each signifier is a trace which is in turn tightly bundled up with différance. and like différance, the trace it is not a word nor a concept – it erases itself as soon as it is named. the difference between signifiers is nothing – it cannot be sensed, and it cannot be comprehended. it is neither present nor absent. the trace somehow evades ontological classification. thus, to name it is misleading, but we must do so in order to discuss it within a system of meaning-making conditioned by the metaphysics of presence. the trace not a static thing but motion itself, in the sense that motion is relational and not objective. it is in motion – “movement of différance”8 – once petrified into a name or concept, that motion, that nonpresence, is no longer adequately described. the trace erases itself.

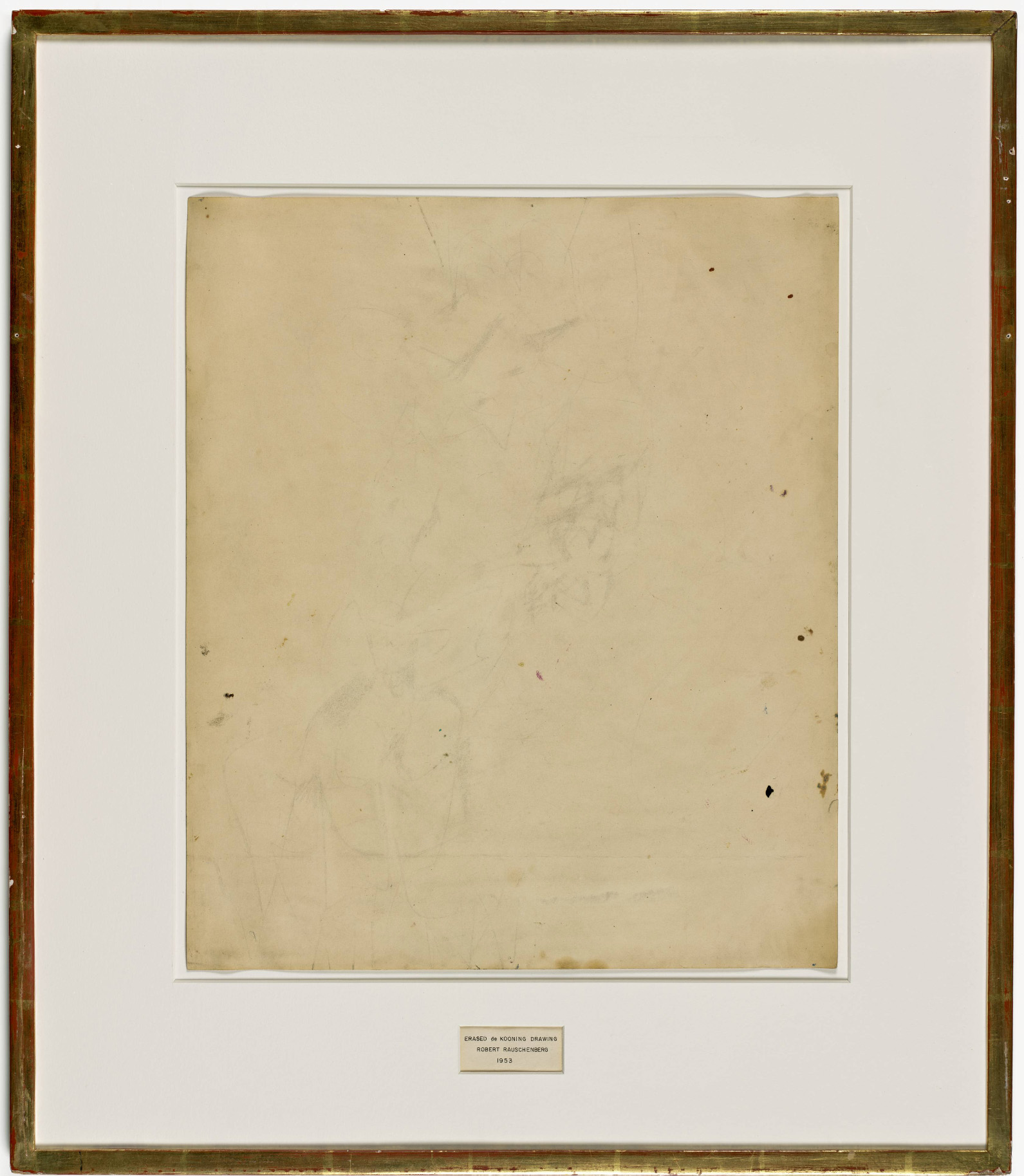

robert rauschenberg, erased de kooning drawing

the trace bears the mark of the other

thus, meaning is emergent out of différance and so the system within which différance is at play cannot be present nor absent, sensible nor intelligible. as such, neither speech nor the “vulgar” notion of writing – as signifier of speech or even as symbolic communication – can comprehend this archaic, fundamental mode of meaning-making. all such notions concern the present, material substance of signification: sound, letters, symbols. instead, derrida proposes archè-writing, or simply writing. for “vulgar” writing is already conceived of as a signifier of a signifier in the metaphysical imagination and this is, in fact, the condition of all language, of all signification, and of all writing. “writing is not a sign of a sign, except if one says it of all signs, which would be more profoundly true.”9

infinitism in the chinese prejudice and the egyptian prejudices

in the early period of modern philosophy, there was broad interest in the possibility of creating a universal script through which all of the peoples of the world could communicate. descartes, kircher, wilkins, and leibniz all wrote on this topic10. within this trend, derrida distinguishes two species: the first sought to develop a universal script based on chinese characters and the second based on egyptian hieroglyphs. elaborating a deconstruction of these projects will be the first step towards understanding the broad implications of grammatology for what is colloquially called culture and politics, though these categories might become suspect upon being subjected to deconstruction.

the first species of projects towards a universal script claimed that a system of symbols, based on chinese characters, could signify “primitive words” which could then be interpreted in any of the languages of the world. descartes provides a clear synopsis of how this might work:

descartes is critical of this project, though only for the practical unwieldiness of such a script rather than for any philosophical concerns. his silence on the issue suggests that he thinks that it could work, at least in theory.

the second species of projects toward a universal script took egyptian hieroglyphs as their base. the proponents of this system believed that, based on the pictographic nature of egyptian hieroglyphs, they could in a sense bypass the phonetic stage and go straight from written symbol to meaning or concept. where the theoretical script based on chinese characters would supposedly be simply read in any language – the same character, for example, could mean tea, thè, çay, чай, 茶, شاي, or चाय depending on the preferred language of the person reading – the theoretical script based on Egyptian hieroglyphs would supposedly skip the middle step alltogether and directly implant something like the “idea” of tea straight into the mind of the reader through the symbol.

while these systems, the latter in particular, might appear to eschew the phonetic bias of which derrida is so critical, they are both in fact deeply embedded within the tradition of the metaphysics of presence. both of these species of projects believe wholeheartedly in the possibility of translation. on a mundane level this seems reasonable: we supposedly translate between languages every day. however, within a grammatological understanding, which emphasizes the trace over the sign, translation is impossible.

why so? both systems rely fundamentally, even more so than traditional scripts, on the notion of the transcendental signified12. this is clearly exemplified in the concept of the “primitive word” to which descartes refers in the paragraph above. if, however, meaning emerges out of différance; if words, sounds, and symbols possess semantic significance as traces; then there is no transcendental signified. translation is impossible because the meaning of a word, sign, or trace within a particular language, dialect, or idiolect is emergent only out of its differences from a whole slew of other words, signs, traces, etc. within that same system. there is no equivalency because meaning is a function of the internal relations of a language. there is no transcendental signified which can act as a yardstick by which “primitive words” can be translated or exchanged between languages.

thus, the cultural and political implications of the trace begin to come into focus. ideas which hold culturally reality are in fact constructed from the internal relations of what could be considered that culture’s dialect of writing. no idea is grounded in a transcendental, immovable signified. in this way, all ideas are unstable: they are subject to change whenever there are shifts within the constellation of signifiers from which their meaning emerges. as noted in the introduction, this philosophy has been famously applied to gender by judith butler. in her book gender trouble, butler deconstructs supposedly transcendent notions of gender and exposes them indeed as constructed or performed13. this technique of deconstruction can of course be applied more broadly and has to some extent embedded itself firmly within the popular imagination. perhaps we can credit derrida to some extent for the oft heard statement “everything is a social construct”.

self-deconstruction

derrida’s fundamental assertation that writing is a system of traces and that meaning is emergent out of difference instead of presence is perhaps not so controversial today. as derrida points out, saussure made this same observation over 50 years earlier, even if he went on to contradict himself and slip back into the metaphysics of presence. what has made derrida controversial is his actual rigorous application of this idea to other fields of knowledge.

despite this, i would argue that some central components of derrida’s philosophy are tainted by the very metaphysical tradition which he seeks to deconstruct, and not just due to his being constrained within a system of writing conditioned by the metaphysics of presence. first and foremost, derrida appears to be limited by the concept of the human despite the fact that he does directly deconstruct this very notion.

for derrida, grammatology questions the name of man14 and deconstructs it. but does he truly take this to heart? derrida chooses writing as a central metaphor for his philosophy, and certainly he has emptied out this term’s conventional sense and filled it back up with new meanings. however, writing most definitely remains a metaphor. and as derrida himself shows us, we must be extremely careful with metaphors. just as the word communication, as a metaphor, colours and warps our understanding, leading us to conceive of communication as physical transmission, so too does the word writing warp our understanding15. the choice of writing – a human-led activity, tightly bound up with language and cognition – as metaphor risks leading us to understanding both the human and the extra-human in terms of experience and subjectivity even if it also leads us to deconstruct these notions. just as descartes did not deny existence outside of the human mind, but inadvertently described everything in terms of the human mind by bracketing it off, privileging it, and endowing it with explaining power, so too is the effect of writing as metaphor.

this danger is particularly acute in light of derrida’s denial of the transcendental signified. of course, the differential character of writing can be applied to both the human and the extra-human, but the metaphor does not take us any closer to understanding the extra-human outside of human experience. however flawed the notion of the transcendental signified may be, it forces us to think the extra-human, and potentially in non-human terms. of course, derrida does not assert that nothing exists outside of the human mind. however, without the transcendental signified and within an understanding conditioned by the metaphor of writing, we might begin to understand the extra-human in cognitive terms. the absence of any direct reference to the extra-human colours, as again we have learnt from derrida himself, the meaning of his philosophy with perhaps even more strength than any presence ever could.

how might a more direct attempt to describe the extra-human colour derrida’s thought in different shades? certainly, his theories could not remain the same. while the transcendental signified would still not exist, writing and the human generation of meaning would be situated within an even broader web of relations. and the inadvertent, subtle, but still very significant bracketing off, privileging, and endowing with explaining power of the human generation of meaning, would be just as arbitrary and just as laden with binary as the very metaphysics of presence that derrida sets out to deconstruct.

✿

1 the metaphysics of presence is a central theme in derrida, but also features largely in heidegger. according to both thinkers, for the entire history of western metaphysics, philosophers have made the mistake of prioritizing presence. for heidegger this is manifest most significantly in a forgetting of the ontological distinction between being and beings. this confusion is quite clear in descartes’ cogito, where the presence of the subject to itself is taken as evidence of being. for derrida this is true as well, though he believes that even heidegger is bound up within this tradition. the notion of being, too, is simply presence masquerading as something different. return to text

2 différance: a derridean play on the word difference combining, in short, the two senses of to differ and to defer into a single term. return

3 de saussure, ferdinand, cours de linguistique générale, quoted in derrida, jacques, of grammatology, trans. gayatri chakravorty spivak (baltimore: johns hopkins university press, 2016), 57. return

4 derrida, jacques, of grammatology, trans. gayatri chakravorty spivak (baltimore: johns hopkins university press, 2016), 13. return

5 derrida, of grammatology, 13. return

6 de saussure, cours de linguistique générale, quoted in derrida, of grammatology, 69. return

7 “grammatology, this thought, would still hold itself walled within presence.” derrida, of grammatology, 101. return

8 ibid, 65. return

9 derrida, of grammatology, 46. return

10 ibid, 82. return

11 ibid, 83. return

12 ibid. return

13 butler, judith, gender trouble (new york: routledge, 1990). return

14 derrida, of grammatology, 90. return

15 derrida, jacques, “signature event context” in limited inc., trans. alan bass (evanston: northwestern university press, 1977). return

✿

butler, judith. gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. new york: routledge, 1990.

derrida, jacques. “différance.” in margins of philosophy, translated by alan bass. chicago: the university of chicago press, 1982.

derrida, jacques. of grammatology. translated by gayatri chakravorty spivak. baltimore: johns hopkins university press, 2016

derrida, jacques. “positions: interview with jean-louis houdebine and guy scarpetta.” in positions. translated by alan bass. the university of chicago press, 1981.

derrida, jacques. “signature event context.” in limited inc., translated by alan bass. evanston, illinois: northwestern university press, 1977.

derrida, jacques. “structure sign and play in the discourse of the human sciences.” in writing and difference, translated by alan bass. chicago: the university of chicago press, 1978.

milesi, laurent. “derrida and posthumanism (i): from sign to trace.” critical posthumanism network, 2020. www.criticalposthumanism.net/derrida-and-posthumanism-i-from-sign-to-trace/.

milesi, laurent. “derrida and posthumanism (ii): the animality of the trace.” critical posthumanism network, 2020. www.criticalposthumanism.net/derrida-and-posthumanism-ii-the-animality-of-the-trace/.

milesi, laurent. “derrida and posthumanism (iii): the technicity of the trace.” critical posthumanism network, 2020. www.criticalposthumanism.net/derrida-and-posthumanism-iii-the-technicity-of-the-trace/.